Goodnight Irene

|

1950 was a very good year for The Weavers. Formed in 1948, the group was only in existence for 4 years and the first couple of them had been marked not only by the familiar penury of musicians, but by political harassment and persecution that would only intensify once they had achieved some prominence. (For a dose of decency and courage in the face of governmental overreach, read the transcript of Pete Seeger's appearance before the House Un-American Committee in 1955.) That prominence began with a Christmas present of sorts—a paying gig at the Village Vanguard during the closing week of 1949. They were such a hit that what was supposed to have been just a weekend stint became weekly, first for the winter, then extended through the spring. That success got them a recording contract and after the obligatory album of Christmas tunes, their second studio session produced a song that hit #1, stayed there for 13 weeks and sold 2 million copies. The song was Goodnight Irene. It's a fascinating recording, one that captures American music at the crossroads between the sophisticated pop of the Big Band era and the roots music that would inform both Rock 'N Roll and the folky singer-songwriters of the decades to come. If you you check out the full recording from which this clip is drawn you can hear Seeger's banjo come in at around two minutes. But not before the string and vocal arrangement has established that this here is serious music.

Audio Clip: The Weavers sing Goodnight Irene, 1950

|

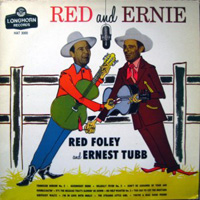

If 1950 was generous to the Weavers, it was even more so to the song itself. That year, Irene just would not say goodnight and go to bed. Maybe that's because she couldn't decide where to lay her head; neither the industry nor the public could settle on a proper home for her. Like the singer of the song who sometimes lives in the country and sometimes lives in town, the song itself wandered between worlds that year and was well received in all quarters. Here are exhibits A and B to back up that claim, both from 1950: first, a countrified version from Ernest Tubb & Red Foley that went to #1 on the Country charts that summer, then yet another by the king of the city-slickers, Frank Sinatra, who waltzed the fair Irene to #12 on the Billboard charts.

Audio Clip: Ernest Tubb and Red Foley on Goodnight Irene, 1950

Audio Clip: Frank Sinatra sings Goodnight Irene, 1950

|

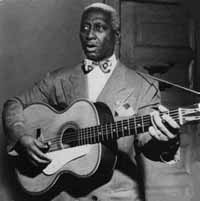

The man credited with writing the song never had a hit with it or with any other. In fact, he never lived to see 1950 or garner any of the royalties the mega-hit would have earned him. He could have used them. Huddie "Leadbelly" Ledbetter had died of Lou Gehrig’s disease in December of 1949, just as the Weavers' gig at The Vanguard was starting and only months before the song took off commercially.

Leadbelly was first recorded singing the song in 1934 while he was still serving time at Angola Prison Farm for attempted murder. The folklorist with the gear, John Lomax, also helped him record a sung petition for his release which was delivered on July 1st, 1934 to Louisiana Governor Oskar K. Allen with Goodnight Irene on the flip side. Later correspondence from a prison official suggests that the recording had nothing to do with it—Leadbelly was eligible for early release due to good behavior by then—but on August 1st, the singer was pardoned.

|

He himself claimed to have learned some version of the song from his uncle Tyrell around the turn of the 20th century. But then, he also claimed at other times to have known the real Irene as a 16 year-old girl. An 1886 song by Gussie L Davis with clear similarities may have been an even earlier source. Still, it was Leadbelly who made Irene the song we know today, with the important caveat that his version was made palatable for a mass audience by The Weavers—and their lead has been followed by most performers who have covered the tune since. It's not hard to understand why. After all, how many of us would have sung along, swaying hand in hand to the original Leadbelly lyric of, I'll get you in my dreams?

Audio Clip: Lead Belly sings and plays his Goodnight Irene

|

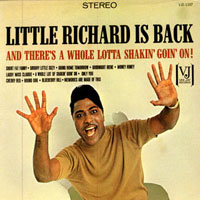

Although many of us have only encountered Goodnight Irene at summer camp and sing-alongs, it has continued to be interpreted by commercial artists both in performance and on recordings ever since The Weavers' wove it into the nation's psyche in 1950. These last few audio clips will attest not only to that simple fact, but to a more important one: that some of those interpretations are surprisingly fresh and engaging. Take Little Richard's performance from his 1965, Little Richard Is Back. The album's title makes reference to the fact that the Architect of Rock 'N Roll had been out of the house he'd helped design for several years at that point, having devoted himself instead to ministry and gospel music. One interesting historical factoid about this recording is that when he made this particular comeback (one of many) he brought with him a young guitarist named James Marshall Hendrix. I wonder if the cool intro was Jimi's idea.

Audio Clip: Little Richard's Goodnight Irene, 1965.

|

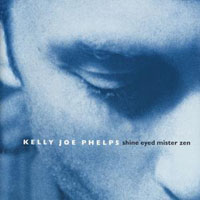

Kelly Joe Phelps' version on his 1999 recording, Shine Eyed Mister Zen, is at once our most intimate and inventive. We've come full circle now to the solo guitar and vocal of Leadbelly's recording, but Phelps throws away everything but the meat of the nut. The melody is unrecognizable; the chord progression is completely reharmonized; even the traditional verse/chorus structure of the song is occasionally disassembled. I don't know if it's the same song as the one Leadbelly wrote, but Phelps successfully gets me to listen to the voice singing it on both his vocal and stringed instruments: the voice of a freshly jilted young man processing his pain alone.

Audio Clip: Kelly Joe Phelps on Goodnight Irene, 1999

Finally, two more triumphs of ingenuity and honesty over the numbing force of familiarity. Both are by contemporary artists I respect immensely, Ry Cooder and Tom Waits. If they still find something to explore in—and express through—this song, you just might want to look for a way to do so yourself.

Audio Clip: From Ry Cooder's 1976, Chicken Skin Music, Goodnight Irene

Audio Clip: Goodnight Irene from disc 2 of Tom Waits' 2006, Orphans: Brawlers, Bawlers & Bastards

All Community Guitar Resources text & material © 2006 Andrew Lawrence